We always welcome interesting conversations, so feel free to contact us if you'd like to get our perspective.

The Lab: 'The powerful interplay of our beliefs and assumptions.' Posts from The Lab

In further reflecting on our conversation at the Lab last month, I found myself wanting to deepen my understanding of what exactly we even mean by ‘assumption’.

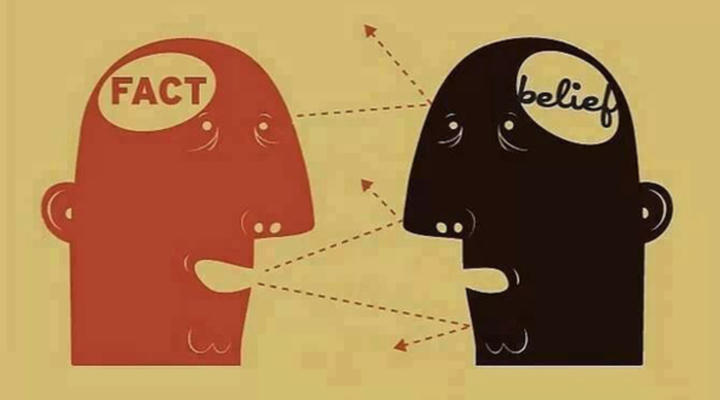

According to the Oxford dictionary, an assumption is ‘a thing that is accepted as true or as certain to happen, without proof’. What struck me about this definition is that it presupposes that we’re conscious of our assumptions. Certainly in many situations this is true – like the explicit assumptions we make about market growth projections. But there are many other cases where we’re not even aware that we’ve made an assumption.

And it’s these subconscious implicit assumptions that are arguably far more powerful and potentially dangerous, precisely because we aren’t necessarily aware of their existence.

These types of assumptions are actually better captured by the Oxford’s definition of a ‘belief’ as ‘something one accepts as true or real; a firmly held opinion’. And indeed, our subconscious assumptions often do stem from our core beliefs. Beliefs about who we are, or are not. Beliefs about what we can or can’t do. And beliefs about what we think is likely to happen to us, or not happen.

Recently, during one of my own professional supervision sessions, I had a powerful insight into some of my own implicit assumptions.

In reflecting with my supervisor about recent client coaching sessions, I realized that I often have an urge to understand my clients’ stories in detail. An urge my supervisor doesn't share. In reflecting further with him, and delving down into the chain of inferences that stemmed from this realization, it became clear to me that this urge of mine is anchored in a belief that if I don’t understand everything, I won’t be able to adequately add value for my client.

In pushing the reflection further, I came to an even more revealing insight. By comparing our respective degrees of ‘needing to understand’, my supervisor and I realized that we held distinctly different assumptions about our ability to understand. My supervisor tends to trust that in time, he’ll come to understand, whereas I tend to fear that I might not…

Why does it matter that I uncovered this particular set of assumptions?

It matters because these core beliefs – at times – create unnecessary anxiety for me. And in addition my assumptions unhelpfully lead me to overly focus on the content of my client’s story, whereas at times it might in fact be more productive to focus on other elements of the conversation.

So let me ask you a few questions to help uncover some of your own implicit assumptions.

Let’s start with some key concepts such as ‘power’, ‘authority’ and ‘money’.

- What is your relationship to authority? What are your underlying assumptions about authority? Where do these assumptions come from? How might these assumptions be showing up in your work environment? Or at home?

- What is your understanding of power? What are your underlying assumptions about power? Where might they come from?

- What is your relationship with money? Do you fear that you’ll lack money at some point in your life, or do you feel confident that you’ll always have enough? Where might this belief come from?

Ultimately, bringing these deep assumptions to the surface is critical. They can have significant influence in terms of the paths we choose, and in the success we ultimately have once we go down a particular path.

So, bringing our conversation back to where it started, which assumptions are helping us in our careers, and which are not?

It’s actually pretty simple.

The helpful assumptions and beliefs are those that make us believe we can successfully travel down the path we most want. Typically, these are beliefs about us having what it takes to become a good leader. Or beliefs that the organisations we work within will support our growth and our drive.

The unhelpful assumptions and beliefs are those that lead us to believe we can’t go down our chosen paths, or are unlikely to succeed if we do. One powerful example is any belief that promotes the idea that leaders are born rather than made.

And while we’re on the topic, there’s extensive research these days showing that there isn’t just one type of ideal leader. It all depends on context. Yes, our genes might help us in some contexts, and may in turn help us to become an ‘emergent’ leader. But there’s no guarantee that the genes we’re born into will make us an effective leader (HBR article "Asking whether leaders are born or made is the wrong question").

What matters more when it comes to being an effective leader is the mindset we bring. Such as the desire to learn and to improve. Or the ability to adjust to our changing contexts. And in particular, the ability to adjust to the different types of people we lead. Leading a 45 year-old Gen Xer doesn’t require the same skills as leading a 30 year-old Gen Yer. And leading a team of experts doesn’t require the same skills as leading a sales team. As our friend and social media specialist John Dobbin said at the last Lab event, the definition of a good leader is itself a ‘morphistic’ concept.

We can always go a step deeper in our journey of self-awareness. Reflecting with others can help us uncover some of our deeply held beliefs and give us an opportunity to challenge them against the beliefs of others.

So let’s keep thinking together…

The Lab is an invitation only event. If you want to join the conversation, drop us a line at [email protected]

Sandra Sieb is a leadership advisor and co-founder of Leadership Partners. More articles on adult development, complexity theory, leadership and system thinking can be found here

This blog is edited by Talia Gill, our brilliant communications specialist :-)