We always welcome interesting conversations, so feel free to contact us if you'd like to get our perspective.

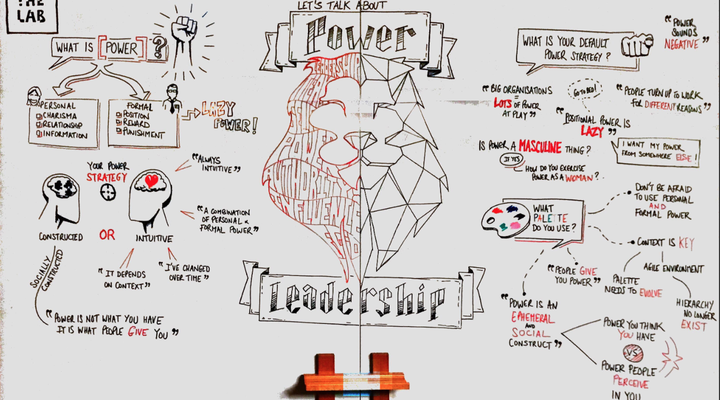

The Lab: 'Reflections on Leadership & Power' Posts from The Lab

Over the past six months, we have held a series of conversations at 'The Lab' with our Sydney- and Melbourne-based communities of inquiry on the topic of Leadership & Power.

Each of these ninety minute conversations have taken us all on a real journey of discovery. Although based on a similar thread, each conversation was unique to the individual stories present in the room on that particular night. Given we explored the theme of ‘Power’ over three sessions, we had a chance to reflect on our leadership behaviours in depth, and gain a better understanding of how we relate to or express power in our own professional contexts.

Childhood experiences are formative

Our first round of conversations was geared towards understanding how each of us as individuals define and relate to power, and perhaps more importantly — where our own particular set of beliefs around power stem from. As the conversations unfolded it became clear just how significant our early experiences of power are in shaping how we view and respond to power and authority as adults.

For some of us, growing up under a dominant power figure — an authoritarian father, an iron-fisted teacher, a dictatorship government — left us with a knee-jerk reaction to rebel against authority. Others admitted to shying away from exerting their own power and influence over others, even in their leadership roles, in response to early negative experiences of power and authority. For others, being on the receiving end of a power differential during childhood had the opposite effect, leading to a firm resolve to become the one holding the power as an adult.

What this underscores is that our individual belief systems — whether they be about ‘power’, or anything else — are a product of both our early life experience and how we respond to these life experiences.

Perhaps surprisingly for a room full of people in leadership positions, what many did share was the opinion that power is often, in one sense or another, something negative. In various participants’ voices, “power corrupts”, “power constraints”, and “power creates fear”. This pervasively negative viewpoint could simply have been a reflection of our specific audience, but it does seem that ’power’ is one of those words that can polarise people. Interestingly though, as one of the participants noted, “...when we talk about a powerful leader, this doesn’t seem to generate the same negative reaction”.

This observation led us neatly into the next round of discussions, which explored more subtle distinctions between the different types of power that exist.

Formal, informal and personal power

Our second round of conversations was a little more structured. Drawing on one of Tim’s favorite topics (‘Positive Organisational Politics’, which he taught at UNSW), we threw in a bit of theory by introducing the notion of power strategies — namely, the different ways that people exert influence over others. We presented the three main distinct types of power people have access to— formal, informal and personal — and encouraged participants to reflect on which type/s they tended to operate by.

Put simply, a power strategy based on formal power is when someone in a position of formal authority, such as a team leader or manager, uses reward and punishment to exert control over others. In this case their ability to exert influence over others stems directly from their formal title or position within an organisation or group — we call this ‘Positional Power’.

In contrast, when a leader adopts a power strategy based on informal power they draw on resources other than their formal position to exert influence over others. Two common forms of informal power are ‘Relationship’ and ‘Information’ power. Relationship Power is the influence a leader gains through both their formal and informal relationship networks. Information Power is the influence a leader gains through using evidence and reasoning to persuade.

Lastly, when a leader adopts a power strategy based on personal power, they draw on personal resources to exert influence over others. ‘Expertise’ and ‘Charisma’ are two common forms of personal power. Expertise Power is the influence a leader gains through their demonstrated ability to develop and communicate specialised knowledge. Charisma Power is the influence a leader gains through their own personal leadership style or persona.

During the conversation, the majority of us voiced a preference for using informal or personal sources of power to lead whenever possible. There was general acknowledgement, however, that at times (and for many of us more frequently than we’d like) we do find ourselves resorting to our Positional Power — both as parents and as leaders. On reflection, many of us agreed that when we did resort to Positional Power, we were often left feeling that we’d failed as leaders — failed to inspire, and failed to motivate. In participants’ own voices, “...it’s not what yields the best in people”, “...the minute people use Positional Power, I rebel”, and “...the use of Positional Power is lazy leadership!”.

There was also acknowledgement, however, that as leaders it’s incumbent on us to ‘own’ our authority — as one participant put it, “when you’re the CEO in the room being aware of your Positional Power is critical, and at times not using it can lead to letting your followers down.”

Power strategies — constructed or emergent?

The last round of conversations delved deeper into participants’ leadership behaviours by introducing the concept of ‘constructed’ and ‘emergent’ power strategies. We say that a power strategy is constructed when the leader thinks about and plans how they will exert their power prior to the event. We describe a leader’s power strategies as emergent when the leader’s behaviour is intuitive rather than pre-planned, and thus literally ‘emerges’ as the event unfolds.

Most of us reported that in our own leadership practices our power strategies were typically emergent, rather than constructed. In saying that preparation was seen as particularly important when using for example Information Power to exert influence, since “building a compelling argument through reasoning and evidence is not something I can do well at a moment’s notice!”.

So, what are our takeaways for leaders?

-

Our early experiences shape how we relate to power. So does our personality. Bringing more awareness to this fact gives you a chance to reflect on whether your approach to power is the most effective one. For instance, being conflict averse might get in the way of you using your Positional Power when the situation calls for it.

-

A diverse range of power strategies exist. As a leader, it pays to be aware of the full breadth of strategies available to you. This allows you to become more cognisant of how you exert influence over others in different leadership contexts.

-

Leadership comes with responsibilities, that of leading. Most of us prefer to motivate and inspire those under our charge through informal and personal channels of influence. At times, however, in order to fulfil our role as leader it’s necessary to adopt a more formal approach to exerting power. Many of us aren’t comfortable with this, but the more comfortable we become, the better we’ll be as leaders.

Our next series of The Lab will be in October - 17th in Sydney and 25th in Melbourne - and we will explore the following question: ‘Can a Leader be too Authentic?’.

If you are interested in participating in this conversation, here are the links to purchase tickets to the next Lab: Sydney or Melbourne.

This article is edited by Talia Gill, our brilliant communications specialist.